Financial traders that do not own generation or serve load can buy or sell energy in most RTOs’ day-ahead markets. Concerns have been raised about financial traders because some believe that much of their activity can be characterized as market manipulation. Indeed, many of the sanctions imposed by FERC enforcement have been against financial traders. Others argue that virtual trading by financial traders plays a key role in providing liquidity in the day-ahead market and causes it to converge with expected outcomes in the real-time market. We seek to answer this question below.

Virtual transactions are non-physical sales or purchases of energy in the day-ahead market that must be sold or purchased back in the real-time market. Hence, they are simply financial contracts and not “real” electricity, which may explain some of the mistrust of virtual trading in the industry. However, virtual trading benefits electricity markets in theory by:

- Providing necessary day-ahead liquidity at otherwise illiquid locations within RTOs’ footprints, which allows the day-ahead market prices to converge with the real-time prices;

- Preventing generators and load-serving entities from exercising local market power at their locations by allowing virtual traders to compete with them (e.g., virtual suppliers can sell in response to a generator withholding in the day-ahead market to increase prices); and

- Allowing the market to reflect the expected value of real-time uncertainties, including forced outages, weather conditions, and load uncertainty.

Ultimately, these benefits all contribute to improved price convergence and, therefore, lead to a more efficient commitment of resources through the day-ahead market and lower costs for all participants. Because most generators require many hours to start and ramp up, the day-ahead market is the primary means to coordinate the commitment of resources.

Although these benefits are compelling, inefficient virtual trading is also possible. We conducted an empirical analysis of virtual trading in MISO in 2016 in order to evaluate the contribution of virtual trading activity to the efficiency of market outcomes. In this analysis, we categorized virtual transactions into those that:

- Led to greater market efficiency by improving the convergence between the day-ahead and real-time markets; and

- Degraded efficiency, either because they led to divergence between the markets or because they profited simply due to modeling inconsistencies between the markets (we refer to these as “rent-seeking” transactions). RTOs must maximize the consistency of its modeling between the day-ahead and real-time market to avoid rent-seeking transactions and associated costs.

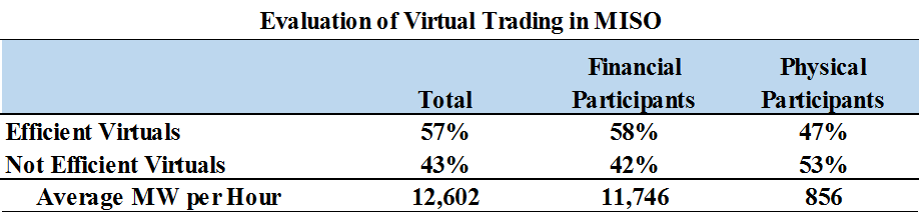

The following table shows the transactions that fall into each of these categories, separately indicating the results for financial participants and physical participants (generators and load-serving entities).

This table shows that 57 percent of all virtual trading volume was efficiency-enhancing and that financial participants accounted for the vast majority of the trading activity. This result is consistent with the conclusion that virtual trading activity overall improves day-ahead market outcomes and lowers costs for all participants. A large share of the virtual transactions do not improve efficiency, but this is expected because the real-time market outcomes are volatile and difficult to predict. Hence, the most beneficial and efficient virtual trading strategy is likely to only be profitable and efficiency-enhancing less than two-thirds of the time.

Furthermore, the table shows that transactions of financial participants are more efficient than physical participants. This may be attributable to physical participants using virtual schedules to hedge risks. This does not raise concerns because trading by physical participants constitute less than 10 percent of the trading volume.

We also quantified marginal benefits and costs of the virtual trading and found that the marginal benefits of the efficiency enhancing transactions of almost half a billion dollars in MISO in 2016. The total benefits would be even larger since profits of efficient virtual transactions shrink and prices convergence improves as virtual transaction volumes increase. In contrast, the rent-seeking profits totaled roughly 30 million dollars in 2016. Again, it is a positive result that these costs are small in comparison to the marginal benefits of the efficient virtual trading.

Importantly, the total benefits are much larger than the marginal benefits and costs we are able to calculate. To accurately calculate this total benefit would require one to re-run all of the day-ahead and real-time market cases for the entire year. Nonetheless, our analysis allows us to establish with a high degree of confidence that virtual trading in MISO is highly beneficial and that financial traders were largely responsible for these benefits.

For a more complete discussion of this analysis, see https://www.potomaceconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2016-SOM-Appendix_Final_7-17-17_final.pdf.